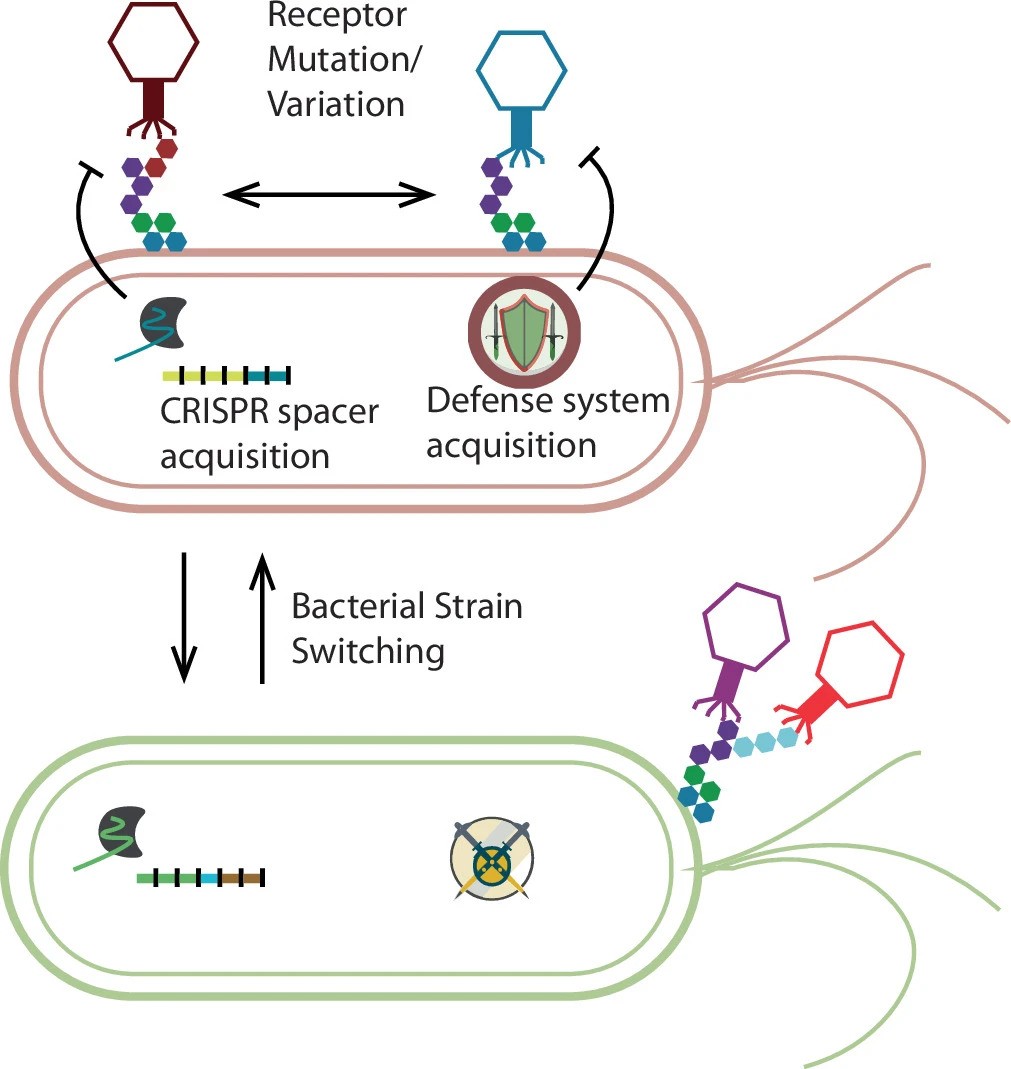

A schematic of factors potentially accounting for high virus (phage) turnover in human guts.

This study explores the dynamic relationship between bacteriophages (phages) and bacteria in the gut microbiome of infants and young children during their early years. Using metagenomic sequencing data from over 12,000 stool samples collected as part of the Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) project, the researchers uncovered how phages and bacteria interact and evolve. Phages, described as the “hidden architects” of the gut ecosystem, exhibit faster turnover and greater transience than bacteria while accumulating diversity over time.

The analysis revealed structured ecological succession in the microbiome, with microbial communities transitioning through distinct phases as children age. It was found that children who later developed type 1 diabetes showed slower changes in their microbial community during their second year of life. By employing the novel bioinformatics tool Marker-MAGu, the study enabled simultaneous profiling of phages and bacteria, revealing a deeper understanding of their co-evolution. Phage profiling also improved the ability to geographically distinguish microbiomes, underscoring their role in shaping microbial ecosystems.

These findings highlight the crucial yet underappreciated role of phages in gut microbiota development and their potential influence on immune system maturation and disease risk. This work not only provides valuable insights into the early-life gut microbiome but also paves the way for phage-based therapeutic and diagnostic strategies.

Figure Description: Since phage often put negative selective pressure on their hosts, these bacteria may evolve evasive mutations in receptor-related genes or other entry factors. Relatedly, some bacteria can conduct phase variation, reversibly altering their surface molecules. Bacteria may also acquire phage-specific CRISPR spacers to fend off deleterious phage or acquire entirely new phage defence systems via horizontal gene transfer. Phage, on the other hand, will sometimes, but not always overcome these new defences via mutation of their own genes. In our study, we are unable to detect bacterial strain switching, in which a new strain of the same bacteria interlopes and outcompetes an existing strain. Strain switching will cause some or all of the bacteria-specific phage to be lost from the gut due to different receptors and defence systems, but it will provide opportunities for new phages. Finally, if a bacterial host becomes extinct, so will its obligate parasite phage, so phages are not expected to persist in the gut for long periods after elimination of its host.

Image Source: Tisza, M.J., Lloyd, R.E., Hoffman, K. et al. Nat Microbiol (2025)

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01906-4